Muon g-2 Experiment

Posted on 25 Jan 2022 by ΔΨφAlmost a year ago, in April 2021, Fermilab announced some rather interesting results regarding the anomalous magnetic moment and the g factor of a muon. However, before getting into that, I would like to start from the beginning and in the process, familiarise you readers with the terminology.

The Magnetic Dipole Moment of a magnetic material refers to its magnetic strength and orientation. This could be produced by the movement of charges such as in a current carrying wire or by the spin angular momentum which is an intrinsic property of elementary particles.

Now, remember the Stern-Gerlach Experiment…………….yes that one, the one I talked about in the Quantum Superposition article. So the year was 1922, and the Stern-Gerlach experiment was to prove the quantisation of space and later went on to give proof of the spin of particles. Remember this was the time when there was no such thing as the “spin angular momentum”.

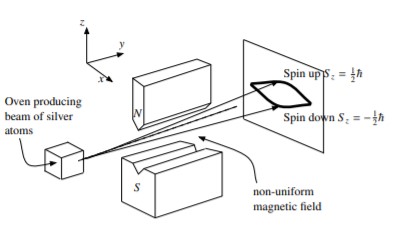

Following is the arrangement of the experiment:

In the experiment, an oven was taken which produced a beam of silver atoms and these atoms were directed to pass through a non uniform magnetic field. The reason for taking a non uniform magnetic field was that in a uniform magnetic field the net torque on the atom would add up to 0 which would not cause any deflection. Finally these deflections would be detected on an observation screen.

The expected outcome of the experiment was that due to random thermal effects in the oven, the magnetic moment vectors of the atoms would be randomly oritented and there would be a continuous spread of the magnetic moments, ranging from \(-\mu\) to \(\mu\). Instead, what was found was that the silver atoms arrived on the screen at only two points that corresponded to magnetic moments of

\[\mu _z = \pm \mu _B\] \[\mu _B = \frac{e \hbar}{2m_e}\]where \(\mu _B\) is Bohr Magneton.

A few years later, Uhlenbach and Goudsmit proposed that electron possessed an intrinsic spin and that in the silver atom the net angular momentum is 0 and the sole source of any magnetic moment is due to the intrinsic spin of the 47th unpaired electron in a silver atom.

This magnetic moment is given by :

\[\mu _S = - \frac{e}{2m_e}gS\]where \(m_e\) and −e are the mass and charge of the electron, S is the spin angular momentum of the electron, and g is the so-called gyromagnetic ratio, which classically is exactly equal to one, but is known (both from measurement and as derived from relativistic quantum mechanics) to be approximately equal to 2 for an electron.

You might notice that this is similar to the relation between magetic moment and angular momentum in the classical sense \(\mu = \frac{q}{2m}L\) where L is angular momentum, but It turns out that the classical result is off by a proportional factor for the spin magnetic moment.

Now this is where the g factor comes in. What is this “g factor”? In simple terms, the g factor is the gyromagnetic ratio without the dimensions. And the gyromagnetic ratio of a particle is the ratio of the particle’s magnetic moment to its angular momentum.

Moving on, we all know that elementary particles don’t actually keep spinning around their axis. Spin is an intrinsic property of fundamental particles that is more closely related to their rotational symmetries. The reason they are said to have a spin is because of the fact that if they are put in a magnetic field, they will spin depending on the particle and the direction of the magnetic field.

In order to understand an electron spinning due to its magnetic moment, consider an analogy of a spinning top. We see that when we spin the top, the top does undergo rotation but it slightly “wobbles” as well, as if some external forces are acting on it. Gravity is an external force which is acting on the top and makes it wobble. Similarly, in the quantum world when there’s a charged particle say an electron spinning around, we realise that there are certain anomalies in its case. These anomalies are due to something called quantum foam which is essentially “virtual” particles popping in and out of existence and interacting with the “real” particles or in some cases the real particles also emit and absorb particles. For example, a particle-antiparticle pair gets produced in vacuum, attracts the electron causing a disturbance and gets annhilated again. This is a typical example of quantum foam in vacuum. All these external interactions result in what we call the quantum mechanical counterpart of the “wobble”. And the measure of this wobble is the anomalous magnetic moment. This anomalous magnetic moment is denoted by a or alpha and is defined as :

\[\alpha = \frac{g-2}{2}\]where g is the g factor

The anomalous magnetic moment and the g factor for an electron are as follows:

\[\alpha = 0.00115965218073(28)\] \[g \approx 2.002318\]The g factor and the anomalous magnetic moment for an electron is known to extraordinary precision and the QED prediction agrees with the experimentally measured value to more than 10 significant figures, making it the most accurately verified prediction in the history of physics.

Further, in the case of the Muon, which can be considered as a heavier version of the electron, the theoretical value of the g factor as found by the Brookhaven Experiment was roughly equal to 2.00233183620(86).

Now coming to what happened in april.

So fermilab carried out this really cool experiment to find out the g factor and the anomalous magnetic moment of the muon. I urge you guys to read about the design and some other details here.

Now this experiment at Fermilab found the g factor value to be 2.00233184122(82) which varied from the theoretical value. The reason this experimental data is so interesting is because it tells us that there is something beyond the standard model that we haven’t even touched yet. This deviation might account for physics beyond the standard model. Although the combined results of Brookhaven and Fermilab show a difference with theory at a significance of 4.2 sigma it still motivates us to dive into this vast ocean and continue our research with ever more enthusiasm and look to explain physics beyond the standard model.

PS : I was busy with my school exams for sometime but I promise to post regular articles from now.

Particle Physics QED